My Insurance Has Denied My Gender-Affirming Surgery. Now What?

Introduction

First, let’s preface this by saying that each trans person’s journey is unique and beautiful and valid. There’s no one right way to transition. You might seek certain surgeries, and not others. You may experience gender dysphoria, but maybe not. All of us have our lived experiences, our ability to access care, our personal wants and needs for our health—and these individual differences shape our journey.

That is why the process of getting a prior authorization or appealing a denial is so exhausting: for too many of us, it feels like a difficult and invalidating experience so that we can get the care we need and deserve. It can feel like an uphill climb to “prove your trans-ness” to your insurance company in order to meet their requirements. For those of us who fall outside the “traditional norms” of what it means to be a trans person, especially non-binary folks, these problems are felt even more strongly.

This guide is aimed at helping you navigate through the framework of a very broken system—and while I could write on and on about everything that’s wrong with the system, that’s not going to be helpful to you. So, I’ll be doing my best to avoid commentary on the nature of the system, and just stick to the facts: we’ll be going over the different types of denials, and I’ll provide recommendations to help understand and navigate next steps.

Understanding Your Denial

The first thing to do is to request a copy of the denial letter.

- Many insurers will send this out automatically—if you’re signed up for paperless, you may need to check your member portal or whatever virtual method your insurer uses to communicate this information with you.

- Read this letter carefully: it will tell you both the reason your request was denied and the next steps you need to take to file your appeal. When filing your appeal, it’s important to operate within the guidelines your insurer provided you to ensure that your request is reviewed for the facts—not for an issue with paperwork.

If your surgeon/physician filed the prior authorization on your behalf, they’ll also get a version of this letter letting them know what the next steps are from their side. Many times, the surgeon will be much better prepared to handle some of the more clinical details of your request, so it’s best to contact your surgeon’s office right away and coordinate with them.

Next, we’ll focus on insurers that do state they will cover transition-related surgeries, but have denied your particular request. There are a number of reasons that a request can be denied, and the course of action forward may vary some depending on the reason you’re given for the denial.

Keep in mind that each insurer is different and each representative you may speak to may have slightly different advice for you when it comes to your case. Sometimes when your request is denied, the easiest thing to do is call in a speak to a representative about why it was denied and what you need to do to get the request approved. They are the experts on their employer’s policies and may be able to guide you on the next steps exactly as it pertains to your case.

1. Prerequisite Requirements Not Met

This can be one of the most frustrating reasons for denial if your doctors and surgeons work under an informed consent methodology. Insurers that pay for gender-affirming surgery typically have requirements that align with WPATH Standards of Care, at least to some extent. What does that entail? Generally speaking, when clinical requirements are not met, such as those set forth by WPATH, it’s best to work directly with your surgeon and other medical providers to get the required documentation to appeal your denial. Your surgeon will be best equipped to look over the specifics of your case and determine what, if any, additional documentation may be needed to overturn the denial.

Physical Health Requirements

These sorts of requirements are likely something that your surgeon or primary care provider (PCP) can address. The best practice—no matter what kind of procedure you’re having or whether or not your insurance is paying for it—is to ensure that your surgeon is aware of any and all pre-existing physical health conditions. Once your surgeon is aware of all of your conditions, they can ensure that their surgical plan properly accounts for anything that may impact the outcome of your procedure. They may also need to consult with any other medical specialists that help you to manage your health, so be prepared to connect your providers.

In some cases, an insurer expects that you must be on gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT, also called HRT) for a minimum amount of time for your type of surgery. A gonadectomy—orchiectomy for trans folks assigned male at birth, or oophorectomy for trans folks assigned female at birth—is the removal of the organs that produce testosterone (testes) or estrogen (ovaries) respectively. If you have not been on HRT for 6 months, or don’t plan to be on HRT at all, your surgeon or primary care physician should be prepared to justify why it is medically appropriate to skip or abbreviate this step. This is not simply a gatekeeping step: UCSF Transgender Care notes that there is an increased risk of osteoporosis (bone deterioration) in transgender folks that undergo a gonadectomy without adequate HRT. So, your surgeon should be prepared to address those risks in your appeal.

Some insurers require HRT regardless of the type of surgery, which can be an especially difficult step for many trans and non-binary folks to overcome. If your transition doesn’t include HRT, regardless of the reason, you and your surgeon will need to be prepared to explain why you do not use HRT. If the decision is medically contraindicated, you will likely have an easier time, but should also be prepared to explain why that contraindication won’t affect your surgery’s outcome. If the decision is your preference, ask a mental health provider to help by providing more detail for your insurer about why or how HRT is not a step on your journey, but surgery is.

Some language provided by WPATH includes:

- Ensure any physical health conditions that could negatively impact the outcome of gender-affirming medical treatments are assessed, with risks and benefits discussed, before a decision is made regarding treatment.

- Suggest health care professionals assessing transgender and gender diverse people seeking gonadectomy consider a minimum of 6 months of hormone therapy as appropriate to the person’s gender goals before the person undergoes irreversible surgical intervention (unless hormones are not clinically indicated for the individual).

Mental Health Requirements

These sorts of requirements can typically be “proven” by way of a letter from a mental health provider with whom you have a therapeutic relationship. Typically, that means you need to have a few sessions with this provider before they’ll write you any sort of letter.

Be careful to check what types of care providers your insurer will accept these sorts of documents from and how many are required. Some insurers will accept letters from Primary Care doctors, but many will require something from a mental health provider. Other insurers require two letters from different mental health providers.

Your mental health provider will typically want to address the length of your therapeutic relationship, any additional mental health diagnoses that you may have and how they relate to your dysphoria. They’ll also typically want to address that you understand that surgery is permanent and non-reversible and that you are of sound mind to make that assessment and to understand the implications of that. If gender dysphoria is not part of your experience, your provider should still attempt to make it clear, from a mental health perspective, why surgery is the best option for you to align your body with your inner self. They should address all aspects of your transition, including non-medical aspects, such as when you changed your name, requested new pronouns, or came out to friends and family.

If you fail to meet any of these requirements, your surgeon can attempt to address why they feel it’s appropriate for you to receive surgery anyway: they may be able to address some of these points themselves, especially as it pertains to consent and ability to understand consent. Unfortunately, however, a lot of insurers don’t budge on this. You may want to consider looking into online-only telehealth services that can provide evaluations over the phone and write a letter on your behalf.

Some language provided by WPATH includes:

- Identify and exclude other possible causes of apparent gender incongruence prior to the initiation of gender-affirming treatments. Ensure that any mental health conditions that could negatively impact the outcome of gender-affirming medical treatments are assessed, with risks and benefits discussed, before a decision is made regarding treatment.

- Assess the capacity to consent for the specific physical treatment prior to the initiation of this treatment.

- Assess the capacity of the gender diverse and transgender adult to understand the effect of gender-affirming treatment on reproduction and explore reproductive options with the individual prior to the initiation of gender-affirming treatment.

- We suggest, as part of the assessment for gender-affirming hormonal or surgical treatment, professionals who have competencies in the assessment of transgender and gender diverse people wishing gender-related medical treatment consider the role of social transition together with the individual.

Other Requirements

Some other recommendations set forth by WPATH have some more cloudy expectations and can be difficult to figure out what they need.

Your surgeon may consider requesting a “peer to peer” with your insurer where they will discuss your case one-on-one with a medical professional employed or contracted by your insurer. This will allow them to get more direct feedback from your insurer about what they’re looking for to approve your case.

The WPATH language includes: “Only recommend gender-affirming medical treatment requested when the experience of gender incongruence is “marked and sustained.”

- This typically means that you must have a documented medical history of being trans for some time. The exact timeframe may vary from insurer to insurer.

- This can be especially difficult to prove if you avoided receiving medical care or had difficulty finding an affirming provider that would properly document your transition, requests, or concerns. It’s also harder if you have opted not to pursue HRT as part of your transition. You are the best judge of which one of your providers will have the best information to respond to this: perhaps you asked your primary care provider about HRT years ago, or maybe you updated your name and pronouns with your therapist and began speaking about it in sessions.

- Consider finding time stamped, non-medical documentation about your social transition to include in your appeal. Perhaps you wrote an email to your extended family years ago informing them about your transition, your new name, or the pronouns you’re using.

- Parents: If your child’s provider refuses to provide trans-affirming care, ask that they at least document in their chart that the child has brought these concerns. This will help to begin a paper trail for your child. Save time stamped communications whenever possible, such as when re-introducing your child to family via a written note, or copies of family holiday cards over the years.

2. Criteria Was Not Met to Prove Medical Necessity

This kind of denial typically means that the insurer has deemed the procedure to be “cosmetic.” Unfortunately, this is far more common for trans-feminine folks seeking breast augmentation, facial feminization, and electrolysis/hair removal, though this denial category is certainly seen across all demographics and surgery types. (This “cosmetic” distinction is also a common way insurers hide an exclusion for gender-affirming surgery, so be sure to read your benefits and covered procedures documentation carefully.)

If the procedure you’ve requested is generally covered by your insurer, but your specific case was denied, chances are your request was missing some of the documentation required to prove that it’s not a cosmetic procedure. You can request a copy of the criteria needed from your insurer and work with your surgeon to see what documentation was submitted and what may have been missed. Once you’ve figured it out, your surgeon can resubmit a request or appeal with the updated information.

If your insurer covers other sorts of “non-cosmetic” gender-affirming surgery, especially related care for another sex (i.e. covers FtM/N top surgery, but considers MtF top surgery to be cosmetic) consider calling your insurer directly and speaking with a supervisor about your case. Try to figure out the details of why your request was denied and request documentation in writing about why the procedure you’re requesting is considered cosmetic.

Even if not officially required, your appeal should include some information from a mental health provider about why the requested procedure is not cosmetic for you.

3. Out of Network Provider

Denials for out of network providers are common for insurance plans that are limited to a certain geographical area, especially if it’s a Medicaid plan or a marketplace plan for “limited network.”

Depending on the type of surgery you’re seeking, it may be difficult to find an appropriate in-network provider. Often, if there are in-network providers for your surgery type, they often don’t specialize in transgender healthcare. A common example is folks seeking FtM/N top surgery (mastectomy) being referred to providers that specialize in oncology care. These providers are not typically prepared to perform the associated procedures for masculinization of the chest, and may also not be the most competent or trans-affirming providers since they are more accustomed to working with cisgender women.

When appealing these decisions, you should first thoroughly research the in-network provider(s) offered to you and be prepared to explain why they are not an appropriate provider for the procedure you’re seeking.

- Try to stick to objective data, such as that the provider is not trained to perform the procedure, the provider has declined to perform the procedure on you, or the provider does not perform the specific procedure that you need (for example, they perform double incision FtM top surgery only and you’re seeking keyhole). Your chosen surgeon may be able to provide some additional information about the procedure you need and why it’s more appropriate for you to see them as opposed to other providers who are available in-network.

- Avoid referencing the aesthetic results in your appeal: while your procedure is deeply personal and you deserve to choose a surgeon that can give you the aesthetic results that meet your needs, your insurance will likely feel that the aesthetic arguments push the procedure into “cosmetic” territory, and will be unlikely to make an exception.

If there are no in-network providers for the procedure you’re requesting, be prepared to explain that. Pointing out that you’ve selected the closest in-network provider or that the provider performs surgery at an in-network hospital can be helpful when appealing. If the provider is not in-network, your insurer may not allow them to bill claims, so if this part of your appeal is approved, you may need to be prepared to pay out of pocket and be reimbursed by your insurer after the procedure and you may need to submit the claim yourself. If you have to submit the claim yourself, be sure to get a thorough list of requirements from your insurer before your procedure. Provide this list to your surgeon and ask them to help provide all the required documentation to submit your claim.

4. Exclusion

Despite medical and legal consensus, many states allow insurance plans to exclude transgender-related healthcare from coverage. This is especially common in the South, the Midwest, and rural areas of the United States.

Benefit exclusions are, without exception, the most difficult to appeal. Many Medicaid and Medicare plans have exclusions on “cosmetic” procedures and with the continued onslaught of anti-trans healthcare bills, these exclusions are becoming more common.

While you can appeal using any or all of the logic and recommendations above, chances are high that your appeal will be denied.

The simplest answer here on what to do next is sadly inaccessible for many of us: you would need to contact a lawyer. Check with your local ACLU or Lambda Legal branch to see if there’s any ongoing litigation against your insurer, employer, state Medicaid policies, or local laws.

Conclusion

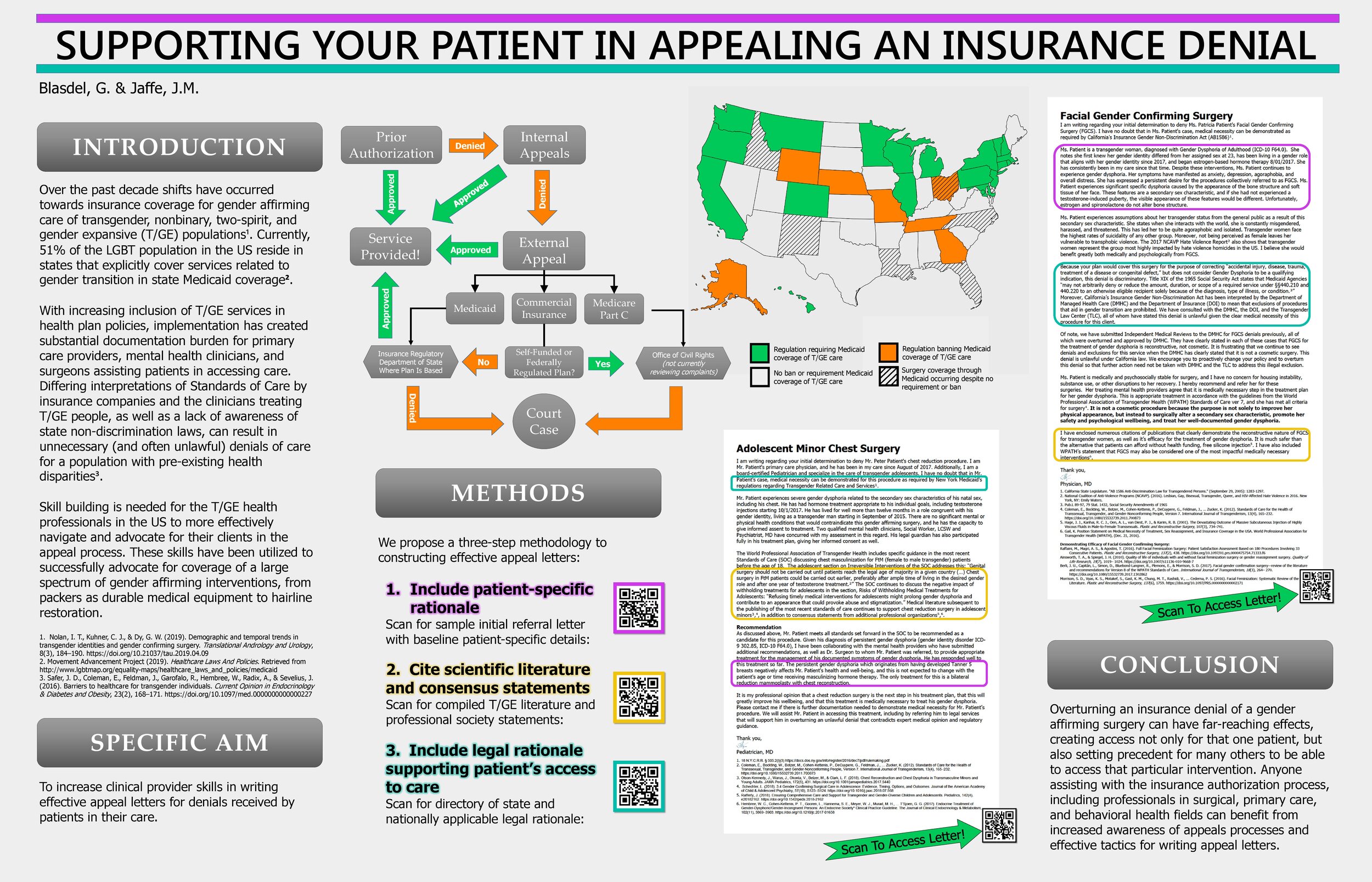

Resources for your healthcare team

The below poster and embedded resources can be shared with your healthcare team. This was created for a presentation at the 2019 United States Professional Association of Transgender Health, Washington, DC. to empower healthcare professionals to better support their patients.

Credit: Blasdel, G., & Jaffe, J. M. (2019, September). Supporting Your Patient in Appealing an Insurance Denial. Download poster as a high-res PDF

Links to embedded resources:

- Appeal Letter Citation

- Regulatory and Legal Citations for Trans Surgery Coverage

- Adolescent Minor Chest Surgery Appeal Template

- Facial Feminization Surgery (FFS) Specific Appeal Template

Closing thoughts

Receiving a denial from your insurance provider can bring up a lot of difficult feelings. No one should be denied access to the care we need for our transition and overall health and well-being. You deserve the best supportive resources available, which is why we suggest considering reaching out to one of these organizations:

- Trans Lifeline: A hotline for trans folks, by trans folks. US: (877) 565-8860. https://www.translifeline.org/ (Note: You do not need to be in crisis to contact Trans Lifeline.)

- Trevor Project: An LGBTQ hotline. US: (866) 488-7386 or http://www.thetrevorproject.org/pages/get-help-now

- GLBT National Help Center: General talkline: (888) 843-4564 | Youth talkline: (800) 246-7743

We also have a growing list of resources that may also be helpful. Remember: you are enough, and you’re not alone.

Written by Tyler Rodriguez

Tyler (he/him) is the Program Manager at Point of Pride. He has worked in the healthcare industry for more than 15 years, and possesses a deep expertise on the issues that most affect our community in accessing care.